Abstract:

In Japan, rural tourism has been promoted for some time, but has few visible long-term positive effects. Researchers centered at Kanazawa University studied rural inn households that use tourism to supplement their incomes. While tourism was found to have environmental and strong social benefits, economic impact was minor. Many proprietors are also aging and lack successors. To thrive long-term, rural tourism destinations need greater competitiveness and would benefit from policies strengthening farming and community building.

Kanazawa, Japan – Tourism has been an economic tool for rural development the world over. Particularly in areas where agriculture has declined, tourists can help activate local economies and improve livelihoods. However, rural tourism’s true impacts on the local environment and communities, and especially on individual households, have been hard to measure and interpret.

Rural Japan, which suffers from agricultural decline and depopulation amid a “super-aging” society, poses unique challenges. The Japanese government has actively promoted “green tourism” since the 1990s, in which tourists visit and enjoy the attractions of rural areas. Yet there are few signs of this having a lasting positive impact; the agricultural sector and rural communities continue to decline.

A team of researchers in Japan, centered at Kanazawa University, deeply examined rural tourism’s impact on farm inns at the household level in the remote western peninsular town of Noto. Noto once had a thriving timber industry and now offers rustic accommodations, providing a humble and authentic countryside experience. The area has recently seen an increase in domestic and foreign tourists.

The research team reported their findings based on in-depth interviews with accommodation providers in the journal Sustainability.

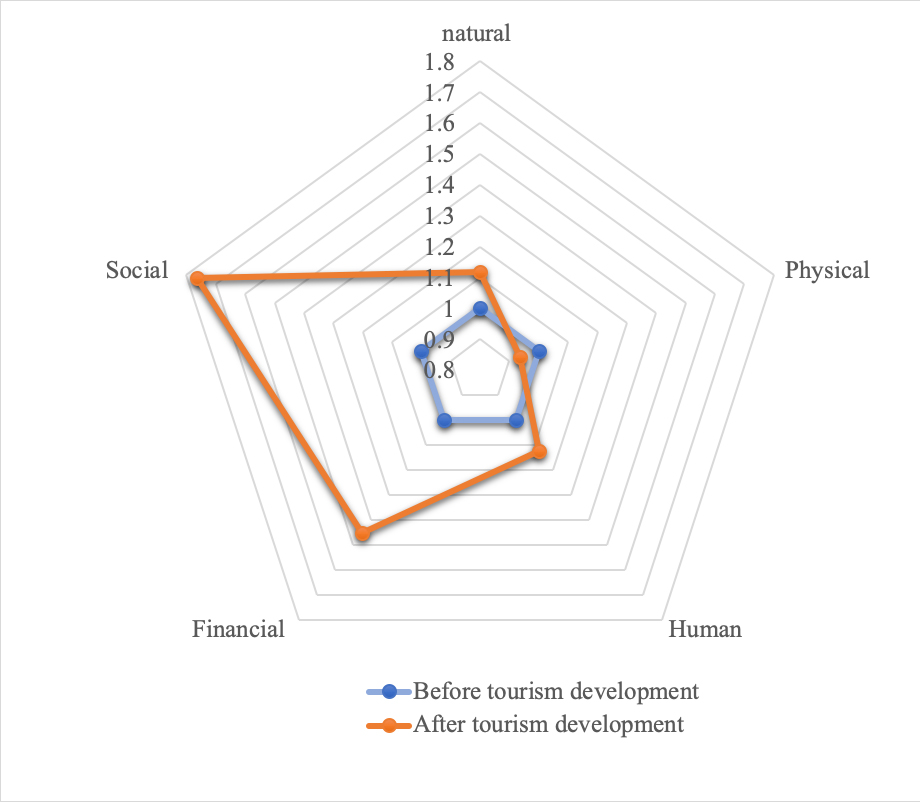

“The average age of inn proprietors in our study in Noto was 70.3 years. They use tourism to supplement their pensions and other minimal income,” one of the co-authors, Prof. Nisikawa Usio said. “We applied a sustainable livelihoods approach to consider physical, natural, human, financial, and social capital all as factors for comprehensively assessing the effects of tourism. We sought to accurately grasp tourism’s impact on the farm inn households, rather than just giving a generalized portrait of the community and environment.”

On the whole, rural tourism’s effects were found to be positive. It encourages preservation of landscapes and use of abandoned farmland. It also creates jobs, an aspect that motivates older people to stay active and preserve their traditions. The social aspects were especially encouraging. Many of the aging workers found it invigorating to engage with the range of visitors, who include foreigners and students.

Conversely, the income generated from tourism industry is quite small, cost spent to repair old buildings need to be subsidized, and competition for guests is also reported among the inns. Seasonality also poses a stiff challenge, as the harsh winters keep most tourists away and visitors peak on holidays and weekends.

Ageing farmers are actively involving in catering for tourists, however, Noto’s greatest looming threat to long-term sustainability of rural tourism is aging. Many inns lack successors and the farmland and environment need to be maintained.

“We found that the local hosts’ quality of life generally improved because of tourism,” another co-author, Dr. Zhenmian Qiu said. “However, economic gains were marginal. Working farmlands and other attractions, strong cooperation and leadership in the community, and governmental support are all keys to rural tourism’s success in Japan into the future.”

Figure 1

Change of capital asset values. Figure 1 illustrates the changes in five livelihood assets before and after participation in a farm inn business. The scale values of natural, physical, and human capital increased on a modest scale, while physical capital experienced a slight decline. In contrast, social capital clearly increased.

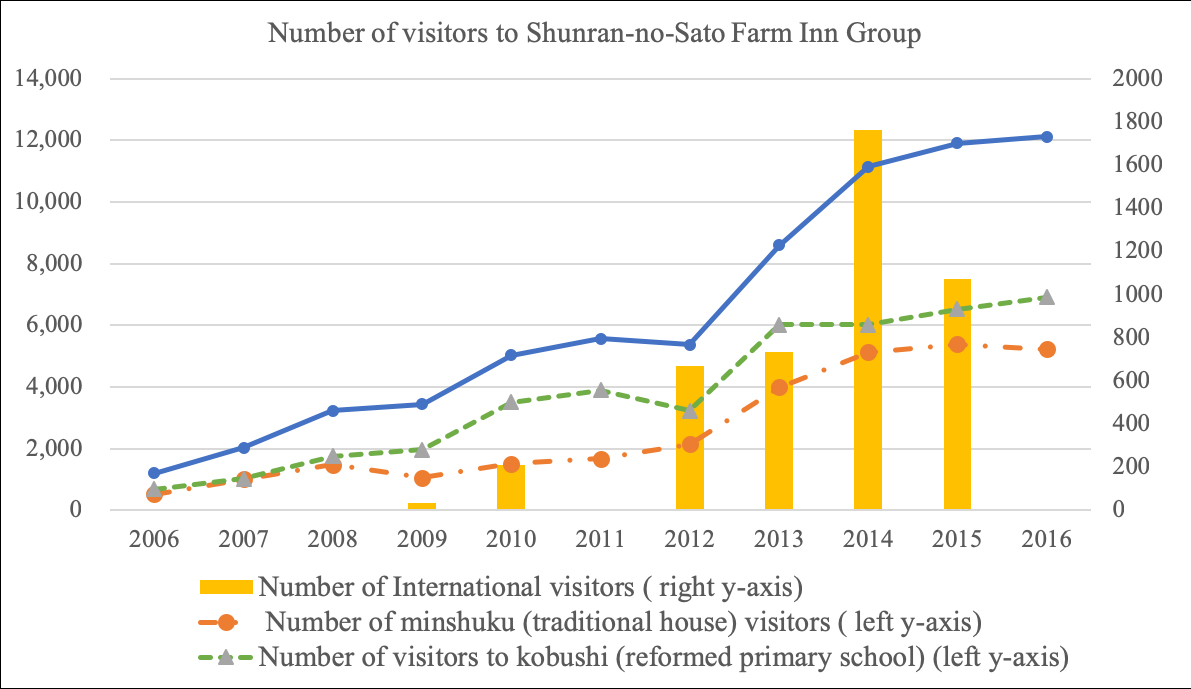

Figure 2

Tourist number increase. Figure 2 illustrates the visitor numbers from 2006–16. The total visitors increased from approximately 1200 in 2006 to over 12,000 in 2016, including those who stayed overnight and day-trippers, or those who engage in service experiences, take baths, and hold meetings. Among these visitors, the number who stayed in traditional houses increased, from approximately 527 in 2006 to 5219 in 2016. Visitors staying at Kobushi also increased, from 681 in 2006 to 6905 in 2016. International tourists also visited the Shunran FIG, and this number increased to over 1000 in 2015. Approximately 10% of all visitors were international, and a majority were from other Asian countries. These visitors were not evenly distributed throughout the year, as the peak season—when group visitors, primarily students, are the most numerous—occurs from June to August. Families and other groups visit on weekends, at the year-end, and on New Year’s holidays; visitors rarely come during the winter.

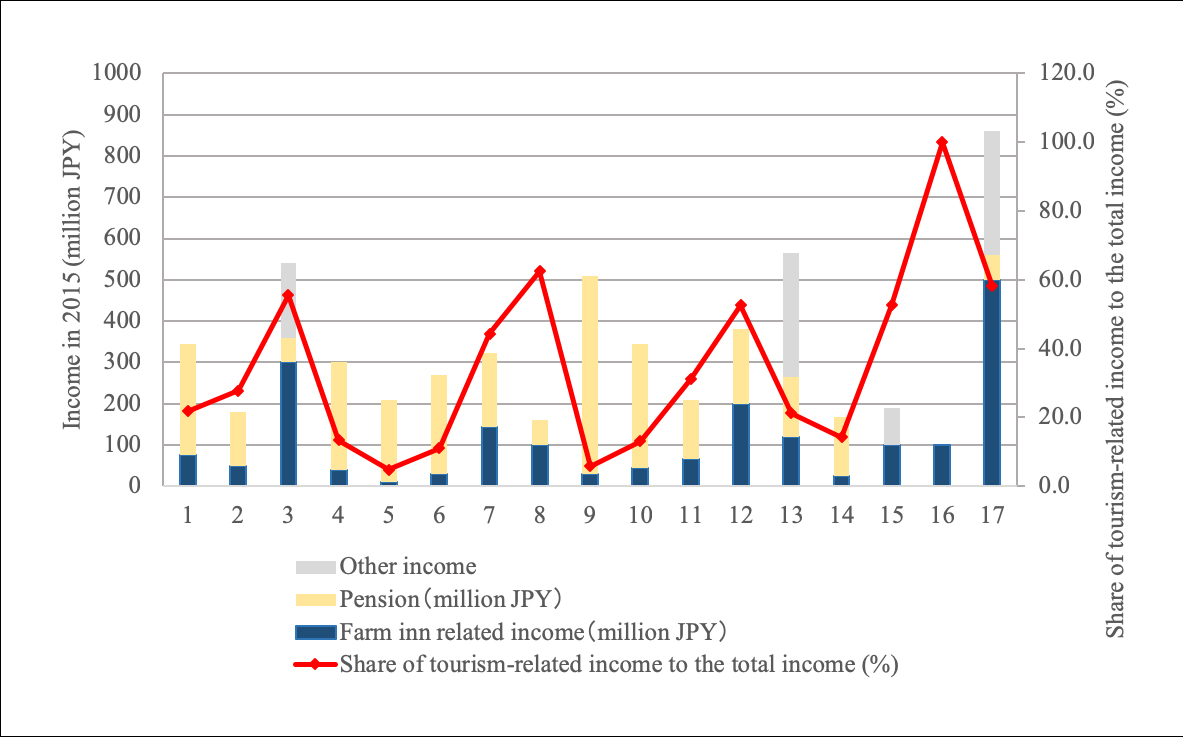

Figure 3

Share of tourism income. Tourism-related income is an important supplement to the household, and respondents’ dependence on tourism significantly varied (Figure 3). Relatively younger respondents who were less than 65 years old were more dependent on tourism-related income than older respondents. Nevertheless, most respondents expressed concern as the annual amount was not high enough, and their supplemental income may vary.

Article

Tourism’s Impacts on Rural Livelihood in the Sustainability of an Aging Community in Japan

Journal: Sustainability

Authors: Bixia Chen, Zhenmian Qiu, Nisikawa Usio and Koji Nakamura

DOI: 10.3390/su10082896

Funders

Part of this study was performed under the cooperative research program of Institute of Nature and Environmental Technology, Kanazawa University (Accept No. 29 in the fiscal year of 2016).

PAGE TOP

PAGE TOP